Brown vs. Board

of Education

This module is divided into three sections.

Did you know?

Deconstruct the topic, define the related concepts, and frame the issue.

Reflect on the impact of the Brown decision.

Why it matters.

Examine the impact on students and educators, teaching and learning; and present a rationale for engaging in actions to redress the marginalizing effects.

Discuss how desegregation efforts have succeeded and failed to secure an equitable education for Black students.

For equity now!

Plan for actions to remedy the marginalizing effects and to disrupt problematic policies and practices.

Plan ways of continuing desegregation efforts in participants current context.

Introduction

In this module, we will explore the historical context of Brown vs. Board of Education, its ongoing implications for present-day school segregation, and the critical role of an equity-based framework in continuing the desegregation work initiated by this historic ruling. Grounded in research and community engagement, this module equips you with a sociohistorical foundation, practical tools, and strategies to navigate the complexities of promoting integration and equity within your schools and districts.

Watch:

Brown v. Board of Education explained

Kenneth Mack, the Lawrence D. Biele Professor of Law, and Meira Levinson, Professor of Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, explain the history of the landmark Supreme Court Case Brown v. Board of Education, the impact the case had on Black education in the United States, and how other movements continue to follow in its footsteps today. Video Courtesy - Harvard University

Kenneth Mack, the Lawrence D. Biele Professor of Law, and Meira Levinson, Professor of Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, explain the history of the landmark Supreme Court Case Brown v. Board of Education, the impact the case had on Black education in the United States, and how other movements continue to follow in its footsteps today. Video Courtesy - Harvard University

Ready to dive deep? Watch the video and answer these questions:

1. What happened immediately following the second Brown Decision in 1954?

2. What were some of the curricular differences between Black schools and White schools?

3. What were some of the ripple effects of the Brown Decision?

A History of In/Equity in US Public Education Policy and Law

The mid-20th century was a period of significant social and political change in the United States, marked by the fight for civil rights and racial equality. Events leading to the landmark Supreme Court case, Brown v. Board of Education (1954), were deeply rooted in the long-standing racial segregation that prevailed in American society, particularly in the education system. Prior to the case, the doctrine of "separate but equal," established in the 1896 case Plessy v. Ferguson, allowed for the segregation of public facilities, including schools, based on race.

The 1930s and 1940s witnessed the emergence of the Civil Rights Movement, gaining momentum with Black activists challenging racial discrimination. One pivotal moment was the 1950 case of Sweatt v. Painter, in which the Supreme Court ruled that separate law schools for Black and White students were inherently unequal. This decision set the stage for the larger challenge to segregation in education.

This photograph shows students at work in the library of Farmville High School, a school for white students Plaintiff's Exhibit No. 3, National Archives Identifier: 75857332

This photograph shows students at work in the library of Farmville High School, a school for white students Plaintiff's Exhibit No. 3, National Archives Identifier: 75857332

In 1951, the NAACP took up the case of Oliver Brown, a Black father from Topeka, Kansas, whose daughter Linda had to travel a considerable distance to attend a segregated school when there was a nearby white school. The NAACP, led by Thurgood Marshall, argued that segregated schools were inherently unequal and violated the 14th Amendment's equal protection clause. The case was consolidated with similar cases from other states and collectively became known as Brown v. Board of Education.

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, declaring that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. The Court overturned the Plessy v. Ferguson precedent, stating that "separate educational facilities are inherently unequal." This landmark decision marked a turning point in American history, striking a blow against institutionalized racism and laying the groundwork for desegregation in other areas of public life.

The aftermath of the Brown decision was met with resistance in many Southern states, where "massive resistance" efforts sought to maintain racial segregation. In 1955, the Supreme Court issued Brown II, which called for the implementation of desegregation "with all deliberate speed." However, progress was slow, and many Southern states continued to resist integration, leading to further legal battles and conflicts.

The events following Brown v. Board of Education were characterized by the courageous efforts of Black students, known as the Little Rock Nine, who faced violent opposition when attempting to integrate Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957. The federal government intervened, highlighting the federal-state tensions surrounding desegregation.

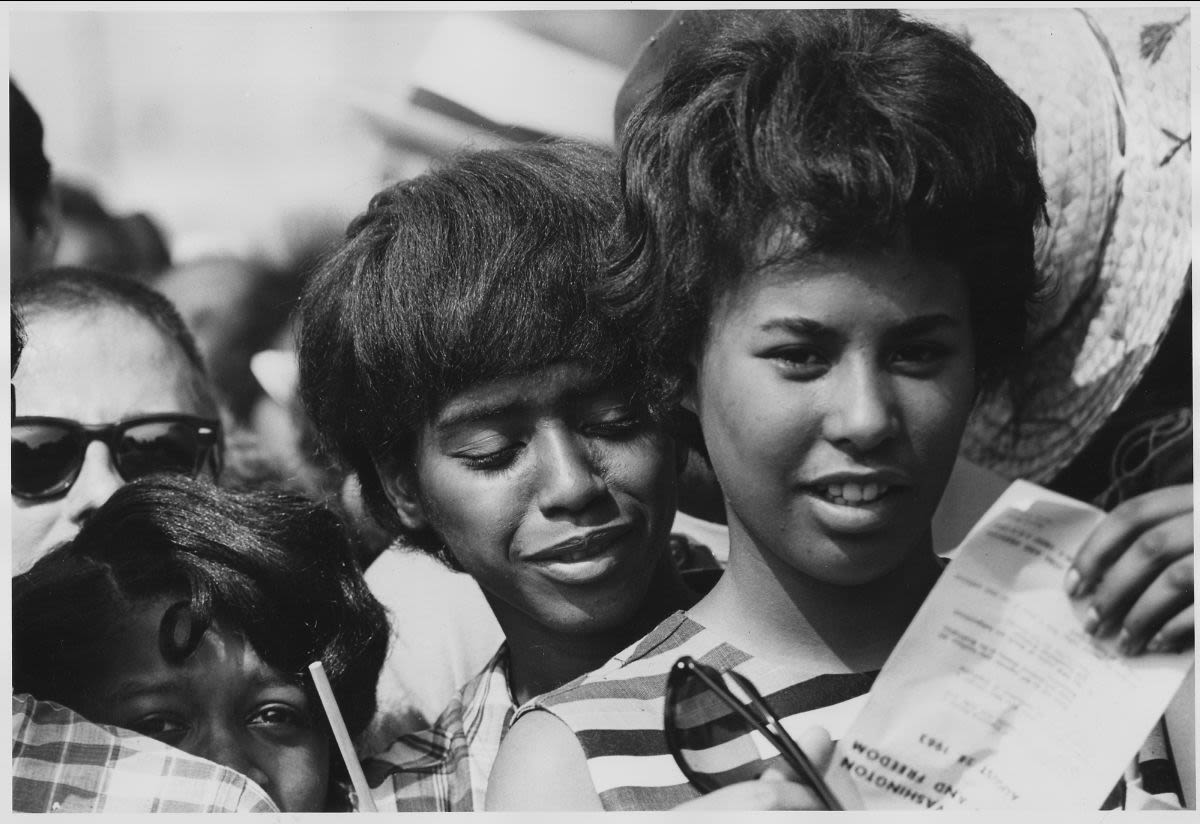

Throughout the 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement gained momentum, with events like the March on Washington in 1963 and the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which aimed to end discrimination in public facilities. The struggle for desegregation extended beyond education, impacting various aspects of American society and challenging deep-rooted racial prejudices.

The events leading to the Brown v. Board of Education were rooted in a history of racial segregation, and the case itself was a watershed moment in the fight for civil rights. While the decision marked a significant victory, the subsequent events revealed the complexities and challenges associated with implementing desegregation. The struggle for racial equality continued to evolve, shaping the broader narrative of the Civil Rights Movement and leaving a lasting impact on the pursuit of justice and equal opportunities for all Americans.

Listen and delve into this podcast below, uncovering Linda Brown's landmark case and exploring the real story behind the Brown v. Board of Education ruling and its profound impact on school desegregation

Comparing Schools

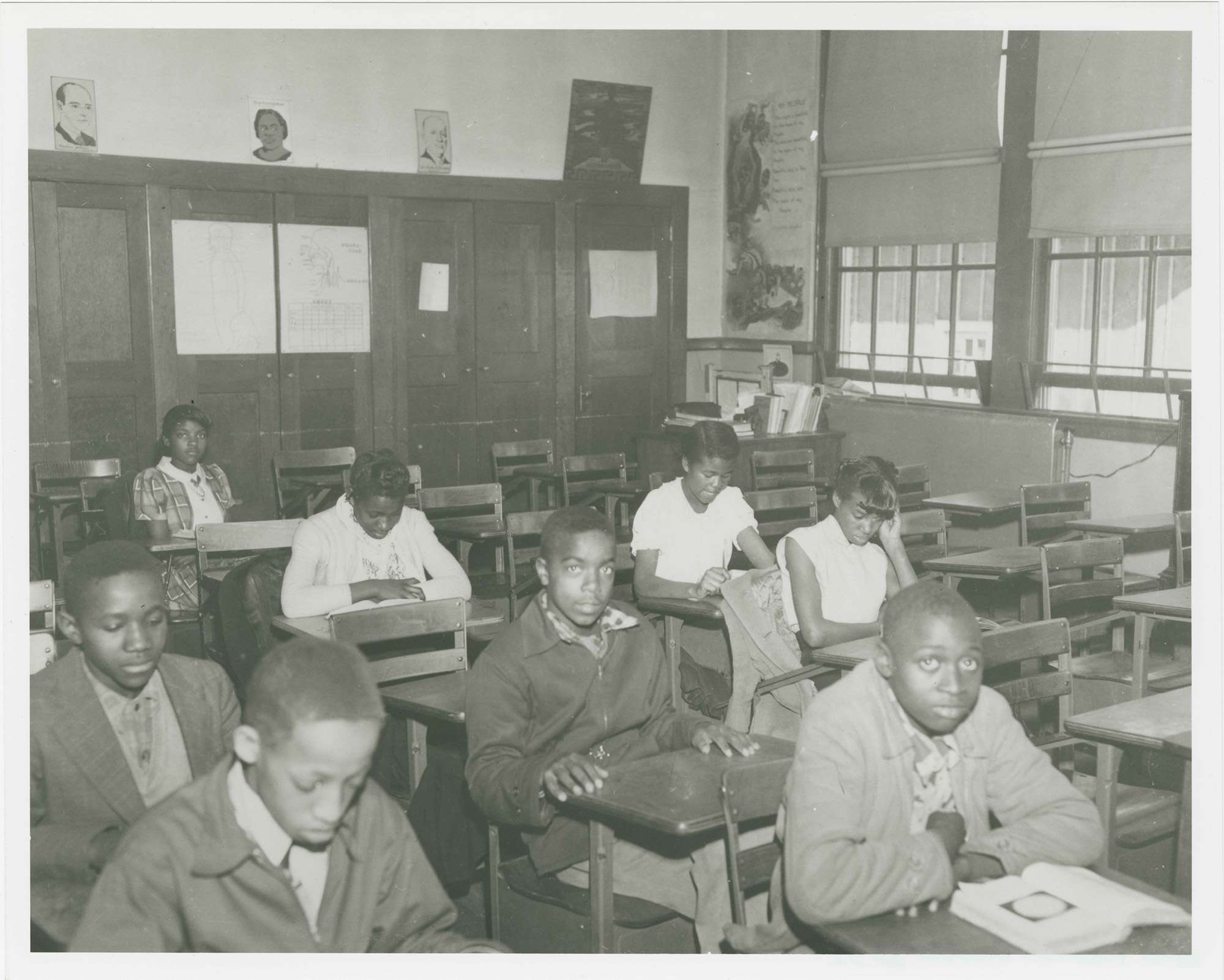

In the face of systemic educational disparities, Black communities confronted numerous challenges that hindered equitable access to quality education. Overcrowded and unsafe school buildings situated far from public transportation posed considerable barriers to attendance. The lack of essential resources, such as desks and textbooks, further exacerbated the educational inequalities. Black teachers, dedicated to their profession, often received less pay than their counterparts, reflecting a stark pay gap rooted in racial disparities.

Rural Black students faced a unique set of challenges, as the demand for farm labor compelled them to attend school for only about four months a year. This limited educational access not only impeded academic progress but also underscored the economic realities influencing Black students' educational experiences. Additionally, the South witnessed a stark absence of universal secondary education for Black students until as late as 1968, highlighting the deeply entrenched segregation that persisted within the educational system.

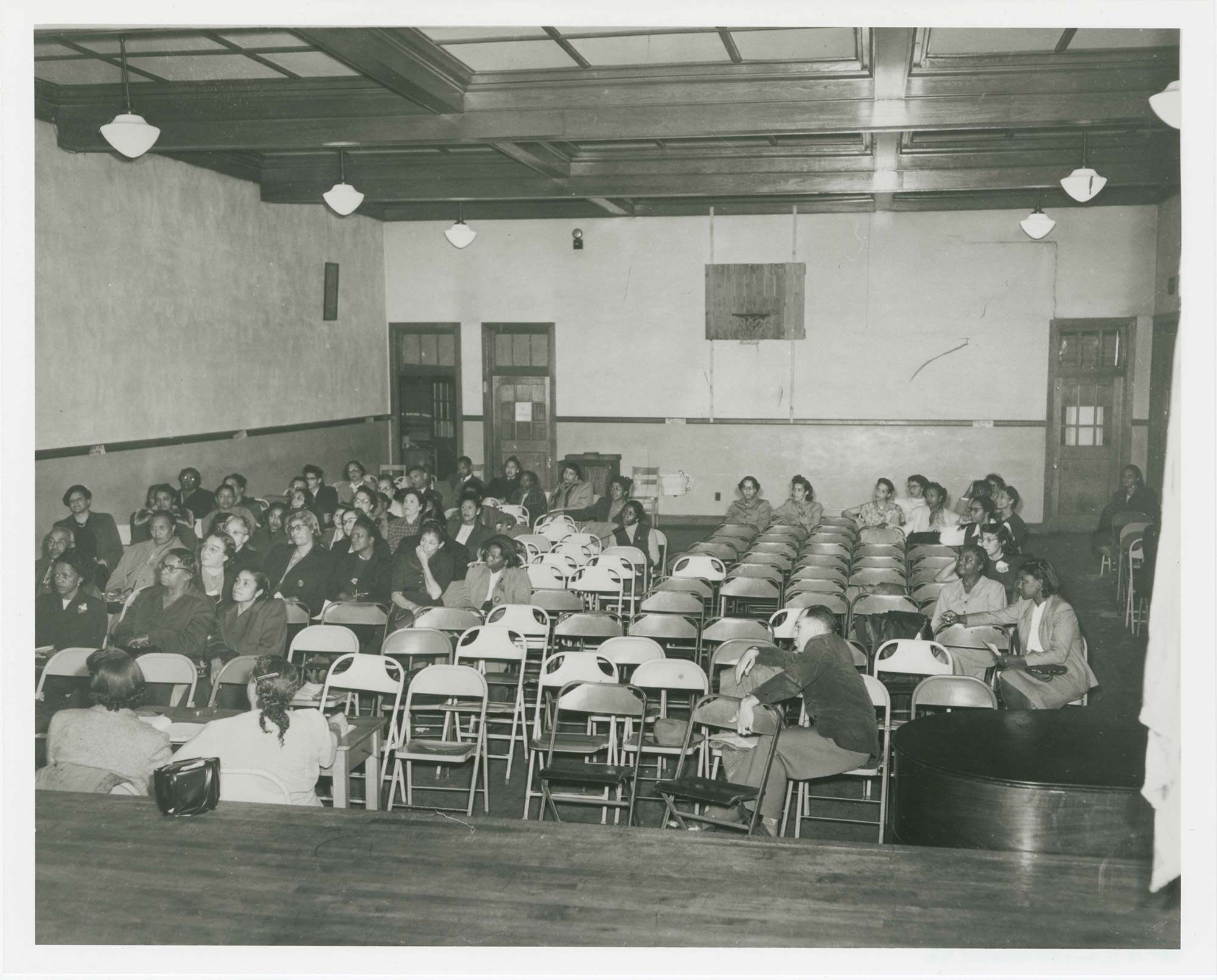

In response to these systemic inequities, Black communities resiliently took collective ownership of their education. During the nineteenth century, literary societies, libraries, and reading rooms emerged as vital spaces for intellectual exchange and knowledge dissemination within Black communities. Black-owned newspapers played a crucial role in providing information and fostering a sense of unity. Emphasizing collective betterment, Black communities recognized education as a catalyst for individual and collective improvement. This commitment to education extended to the tradition of influential Black leaders such as W.E.B. DuBois, Anna Julia Cooper, Carter G. Woodson, and others, who played pivotal roles in advancing educational discourse and advocating for equal opportunities.

Unintended Consequences

The impact of desegregation on the Black teaching and school leadership workforce has been profound, leaving enduring effects felt in contemporary education. In de jure segregated states, where racial segregation was legally enforced, up to 50% of the educator workforce was Black (Will, 2022). However, the push for desegregation decimated this once robust pipeline of Black educators, leading to a significant decline in their representation. This depletion not only disrupted opportunities within the Black middle class but also created a void in the educational landscape, affecting the mentorship and guidance available to Black students.

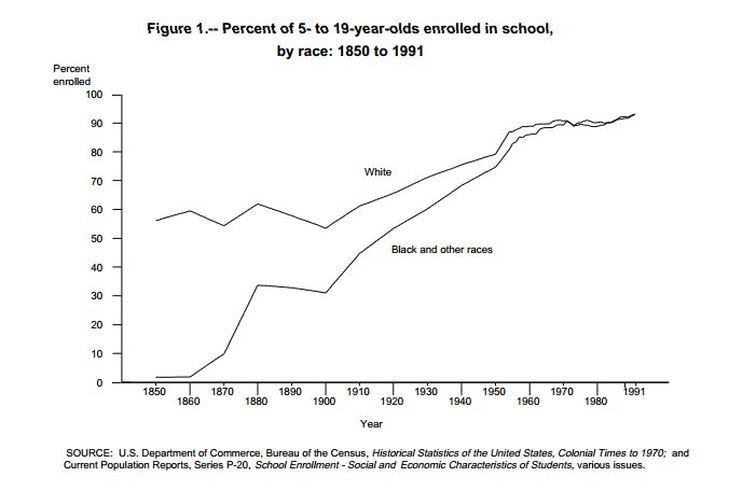

This graph illustrates black students' school enrollment from 1850-1991. Note that after the Brown v. Board of Education decision, black students' enrollment begins to approach school enrollment of white students. This is not to suggest that black children did not receive a robust education within Black communities, but to illustrate how segregation excluded black children from public education as we know it today.

This graph illustrates black students' school enrollment from 1850-1991. Note that after the Brown v. Board of Education decision, black students' enrollment begins to approach school enrollment of white students. This is not to suggest that black children did not receive a robust education within Black communities, but to illustrate how segregation excluded black children from public education as we know it today.

Today, Black students often find themselves taught by white teachers, some of whom may have opposed the very desegregation efforts that aimed to dismantle racial barriers. This lack of representation and cultural understanding has consequences, contributing to disparities in educational experiences.

The absence of teachers who share similar backgrounds and experiences can lead to a failure in establishing high expectations for Black students. Despite these challenges, Black communities continue to foster Black education traditions. Initiatives such as Freedom Schools, the Black Panther Party's educational programs, the NAACP, and the role of Black churches demonstrate the historical and contemporary commitment to preserving and advancing educational opportunities within the Black community. These efforts reflect a determination to overcome the obstacles created by desegregation and sustain a legacy of educational empowerment.

Fact or Fiction?

Portions of this content appeared previously in “Furthering School Integration Efforts in Local Communities: A Professional Development Manual for School District Stakeholders” by Sarah Diem, Sarah W. Walters, & Madeline W. Good.

Diem, S., Walters, S. M., & Good, M. W. (2022, February 11). Furthering School Integration Efforts in Local Communities: A Professional Development Manual for School District Stakeholders. Great Lakes Equity Center. https://greatlakesequity.org/resource/furthering-school-integration-efforts-local-communities-professional-development-manual

It has been 70 years since the Brown Decision, and yet, the work of desegregation continues. Test your knowledge below and learn how segregation still occurs in public schools.

Test your knowledge: Is this fact or fiction?

Fiction:

While there is not an accurate count of how many exist, there are a number of desegregation orders still in place across the United States, with estimates ranging from 150-350 (A.P., 2019; Ujifusa & Harwin, 2018).

School segregation largely happens due to “de facto” segregation, segregation that occurs "by fact," as a result of societal differences between groups such as race or socio-economic status rather than through the law.

Fact or fiction?

Fiction:

The false belief that “de facto” segregation is the motivation behind school segregation is a common and harmful narrative that often erases the influence of “state-sponsored” laws and policies that have created segregated schooling throughout history (Erickson, 2016; Rothstein, 2019).

Black students were not receiving a quality education prior to school desegregation.

Fact or fiction?

Fiction:

Even with resource disparities prior to desegregation, there were many exemplary Black schools staffed by high-quality Black teachers (Fairclough, 2004; Walker, 2000). Desegregation efforts broke up many of these spaces causing Black teachers to lose their jobs, perpetuating the false belief that Black schools were inherently lower in quality as opposed to under-resourced (Hudson & Holmes, 1994).

Issues around segregation, desegregation, and integration are relevant in urban, suburban, and rural school districts.

Fact or fiction?

Fact:

While much research in this area has been conducted primarily focusing on urban areas, suburban and rural districts continue to be influenced by issues around segregation, desegregation, and integration (Logan & Burdick Will, 2017; Orfield & Frankenberg, 2008).

Schools can be integrated based on criteria that includes more than race/ethnicity.

Fact or fiction?

Fact:

Other student characteristics, such as student socioeconomic status, Census tract data, and housing location, for example, can be used to help integrate public schools (Chang, 2018; Frankenberg, 2018).

There is no support for school desegregation at the federal level.

Fact or fiction?

Fiction:

In the fall of 2020, the U.S. House of Representatives passed an amendment reinstating the Strength in Diversity Act, which focuses on incentivizing school districts to reduce racial and economic isolation in their school buildings (Strength in Diversity Act of 2020; Ujifusa, 2020).

We tried desegregation. It didn't work.

Fact or fiction?

Fiction:

There are important “success” stories in regard to desegregation that are often overlooked in public discussion, such as in Louisville, Kentucky and Hartford, Connecticut. Yet, there are also examples of “failed” desegregation. It is important to remember, however, that many of these “failures” were due to issues that could have been addressed, such as undue burdens placed on Black and Brown families and resistant district leaders actively working to make school integration an impossibility (Erickson, 2016, 2019; Quick, 2016).

Increasing school choice options creates more equity.

Fact or fiction?

Fiction:

Incorporating “choice” options in districts does not guarantee educational equity. In fact, there is clear evidence that uncontrolled school choice leads to further segregated schools (Jennings, 2010; Shaffer & Dincher, 2020).

School integration is a pressing issue today, even if many argue that it is only an issue of the past.

Fact or fiction?

Fact:

While current school segregation rates are still being debated in research, there is general consensus that racial isolation and segregation is a pertinent and urgent issue in U.S. education today (Johnson, 2019).

School Segregation Today

Portions of this content previously appeared in “Staying the Course for School Desegregation: Leveraging New and Prior Efforts” by Sarah Diem and Brittany Smotherson.

Diem, S., & Smotherson, B. (2022, September 7). Staying the Course for School Desegregation: Leveraging New and Prior Efforts. Great Lakes Equity Center. https://greatlakesequity.org/resource/staying-course-school-desegregation-leveraging-new-and-prior-efforts

As we delve into the legacy of Brown vs. Board of Education, it's crucial to recognize how its impact reverberates through present-day realities. We must understand that despite the legal victories of the past, segregation persists in subtle yet insidious ways within our education system. From disparities in funding and resources to the clustering of students along racial and socioeconomic lines, the experiences of countless learners today continue to be impacted by segregation. By acknowledging these ongoing challenges, we are empowered to confront them head-on and work towards building truly inclusive and integrated learning environments for all students.

The majority of respondents on a recent US survey about school integration felt it was important for public schools in their communities to be both racially and economically diverse (Potter et al., 2021).

A large number of school districts and charter schools are working to combat segregation in their school communities by implementing school integration policies or other legal measures (Anderson & Frankenberg, 2019; Potter et al., 2021). Although many families value the idea of diverse schools, their actions can look quite different. This is particularly true for White families who support racial and economic diversity but do not send their children to integrated schools because they perceive them to not be as “good” or of “high” quality (Billingham & Hunt, 2016; Roda & Wells, 2013; Torres & Weissbourd, 2020).

Listen:

Separate and Unequal Schooling Today

Ready to dive deep? Listen the podcast and answer these questions:

1. What are the differences in student experiences between the two schools?

2. How does segregation harm students in under-resourced schools?

3. How did the exchange program illuminate disparities for the students?

4. How do well-meaning teachers miss the mark in their efforts to support students in disinvested communities?

Case Study: New Jersey

Case Study: St. Paul

A Framework for Equity

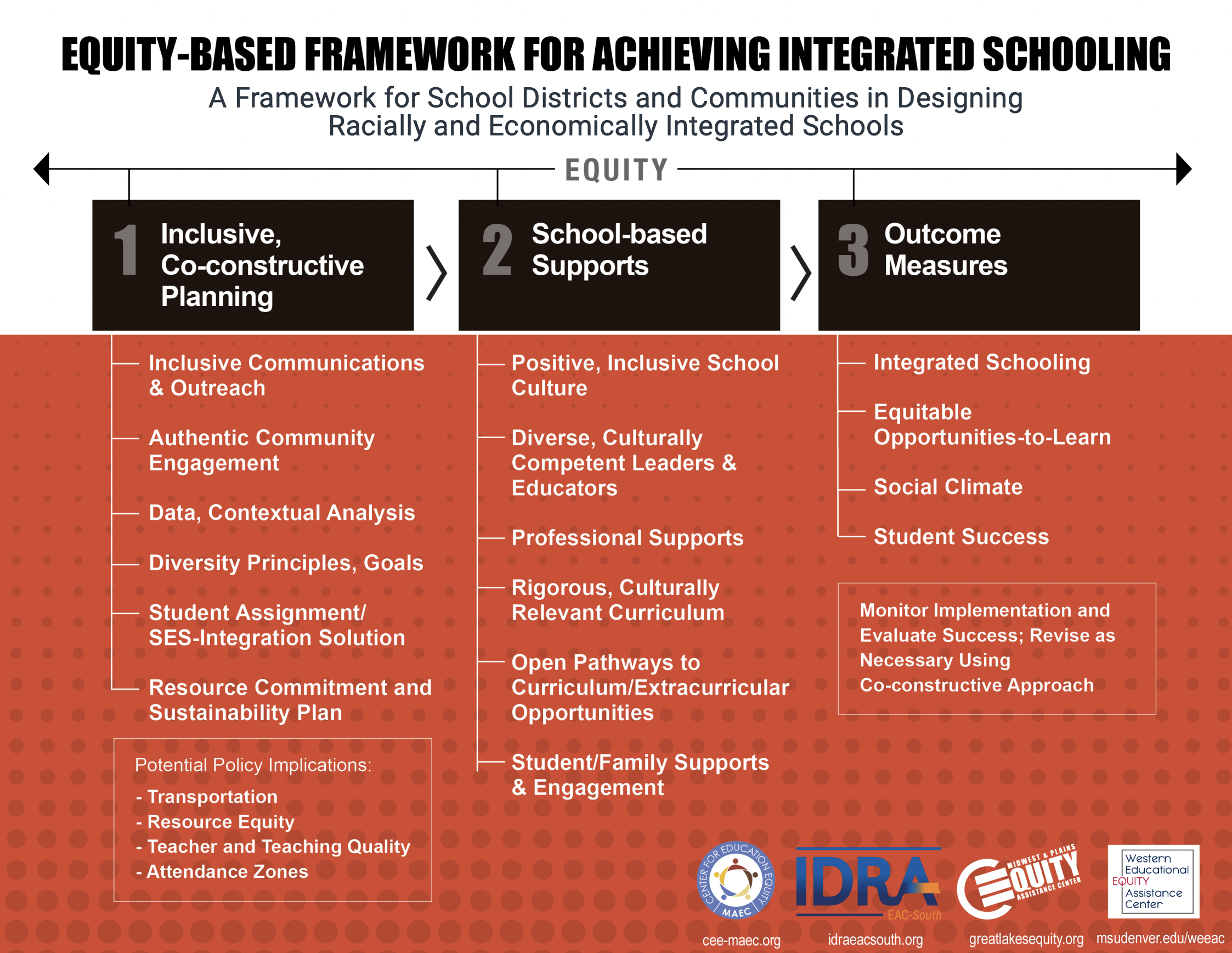

Educators committed to advancing equity in education recognize the significance of employing an equity-based framework to further the desegregation work initiated by Brown vs. Board of Education. By utilizing a research-based framework, we can structure our efforts around strong practices and community engagement. Such frameworks provide a roadmap for fostering inclusive planning processes, implementing school-based supports, and measuring outcomes—all crucial elements for intentionally dismantling systemic barriers to integration. Thereby, we not only honor the legacy of Brown but also actively contribute to the ongoing pursuit of educational equity for all students.

About the Framework:

- Inclusive, Co-constructive Planning

- School-based Support; and

- Outcome Measures.

https://greatlakesequity.org/resource/equity-based-framework-achieving-integrated-schooling

Central to the framework's design is its flexibility, allowing local communities to tailor its implementation to their unique needs and aspirations. Recognizing the diverse landscapes of education across regions, the framework does not prescribe a rigid, step-by-step process. Instead, it empowers communities to engage authentically in inclusive planning processes while ensuring equitable access and opportunity for all students. At its core, the framework champions the principles of diversity, inclusion, and community partnership as catalysts for achieving integrated schooling. We urge educators and constituents to leverage the Equity-Based Framework as a practical tool for enacting systemic change within their schools and districts. By embracing the framework's foundational components and support strategies, we can foster environments where every student feels valued, supported, and empowered to succeed.

Equity-Based Framework for Achieving Integrated Schooling. (2018, November 28). Great Lakes Equity Center. https://greatlakesequity.org/resource/equity-based-framework-achieving-integrated-schooling

Conclusion: Advancing Equity in Education

As we reflect on the legacy of Brown vs. Board of Education and the ongoing journey towards educational equity, it is imperative to acknowledge both the progress made and the challenges that persist. The landmark ruling marked a pivotal moment in United States history, challenging the systemic racism ingrained within our educational institutions. However, despite the legal mandate for desegregation, disparities in educational opportunities and outcomes persist along racial and socioeconomic lines. As we move forward, it is crucial to recognize that achieving true equity requires a multifaceted approach that addresses not only the perceivable manifestations of segregation but also the underlying structural inequalities that perpetuate them.

At the heart of our mission at the Great Lakes Equity Center, and in particular our Region III Equity Assistance Center lies a commitment to dismantling these barriers to equity in education. By providing resources, training, and support, The Midwest & Plains Equity Assistance Center strives to empower educators, administrators, and community members to create inclusive learning environments where every student has the opportunity to thrive. Our work is rooted in the belief that education is not only a fundamental right but also a powerful tool for social change. Through collective action and advocacy, we can work towards a future where educational equity is not just a lofty ideal but a tangible reality for all youth, regardless of race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status.

As you continue your journey toward creating more equitable schools, we encourage you to utilize the resources provided in this session and explore the myriad tools, strategies, and frameworks available through the Great Lakes Equity Center and the Midwest & Plains Equity Assistance Center. Together, let us seize this moment to build upon the legacy of Brown vs. Board of Education and ensure that every child receives the quality education they deserve. By embracing the principles of equity, diversity, and inclusion, we can create transformative change in our schools and communities, laying the foundation for a more just and equitable society for generations to come.